5 minutes read.

Beyond the spotlight, dive into the untold history of Los Angeles at LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes. The permanent exhibition “L.A. Starts Here” brings to life the hidden stories of Mexicans and Mexican-American, offering a fascinating narrative that spans from the Tongva Native Americans to Spanish colonization, the Californio rancho era, independence from Spain and Mexico, and early 1900s immigration. Unlock 100 years of chronicles and discover the events that shaped Los Angeles into the culturally diverse city it is today.

Tvonga Native Americans

Archeological evidence shows that the Tvonga lived in the Los Angeles area for 1,500 years. It is estimated that 300,000 Native Americans lived in California in the late 1800s, and around 5,000 in Los Angeles.

Tvonga spread in 50-100 communities across present-day Los Angeles County.

Did you know?

The Tvonga are not currently a federally recognized tribe.

1781 – Spanish colonization

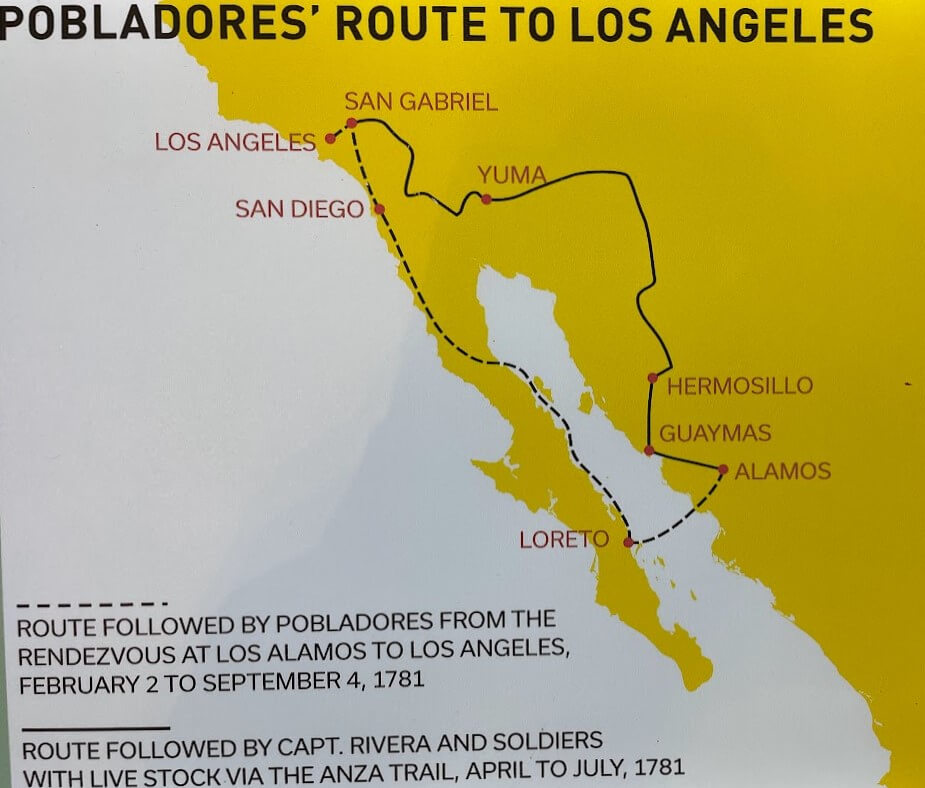

Competing to explore and conquer North America, Spain was rivaling with other nations like England and Russia. To expand Spanish authority in the region, King Carlos III ordered Felipe de Neve, governor of Spanish California, to establish settlements with pueblos (towns), missions, and presidios (military bases).

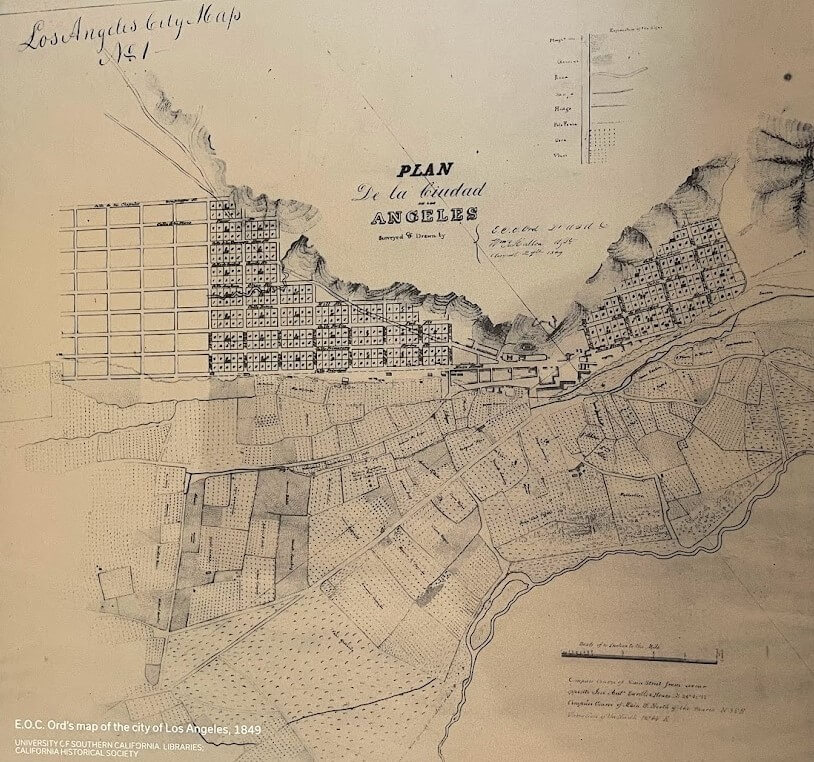

It took two years for Felipe de Neve to gather 44 people to move from Mexico to the Los Angeles area. Promising lands and tax exemptions, these Spanish Pobladores (citizens) established the Pueblo of Los Angeles in 1781.

Did you know?

Early explorers believed that California was an island.

Settlers established property concepts and introduced new crops, agricultural practices, animals, and diseases. These environmental changes significantly impacted Native American ways of life, including their food sources, culture, and traditions.

With missions established along El Camino Real, Spaniards converted Native Americans and used them as a workforce to develop their economy and consolidate control in the region.

Did you know?

Pobladores received 2 reales per day and 10 pesos per month for their journey from Mexico to Los Angeles.

Mid 1800 – Californios landowners

In California, The Spanish crown distributed 8 million acres of land, splatted over 700 private land grants.

Many Californio landowners became prosperous families as they developed cattle ranching for hides, tallow, and meat. California produced raw materials for Spain and imported manufactured and luxury goods. This system supported by Spain, will later unfavorably impact California after the Mexican independence.

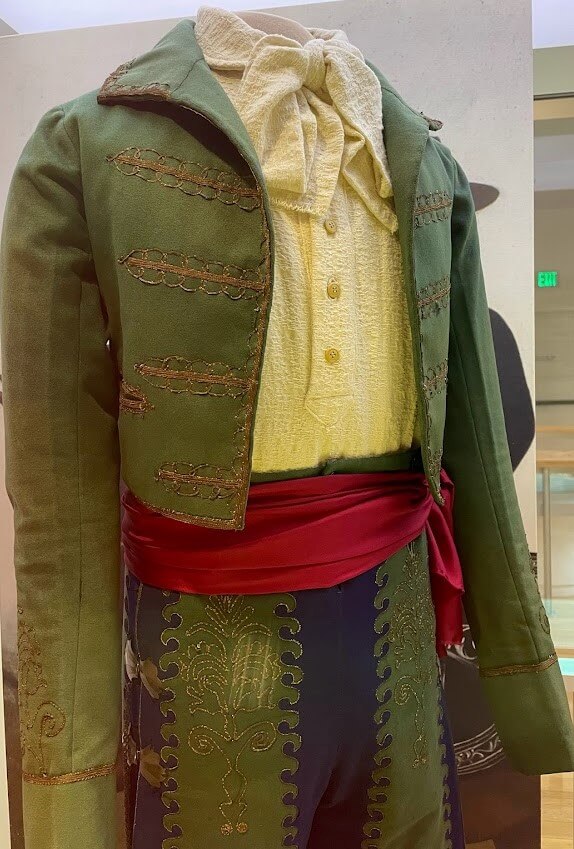

The life of Pío de Jesús Pico mirrors the development and decline of California. Born at Mission San Gabriel Arcángel in 1801, Pío Pico’s parents were mestizos: a mixed heritage of African, Native American, Spanish, and Italian ancestry.

Pío Pico began his political career in San Diego, then participated in a revolt against California Governor Manuel Micheltorena. In 1845 he became the last governor of Mexican California, following a brief term in 1832.

He moved the capital from Monterey to Los Angeles, politically and economically transforming the original pueblo into a dynamic city. During this time, Pío Pico was one of the wealthiest men in California, thanks to his involvement in politics, business, and livestock farming.

Did you know?

Pío Pico owned over 500,000 acres of land.

Pico’s political career ended in 1846 with the American conquest. Subsequently, he faced significant financial losses due to racism, lawsuits, and debts. By the time of his death in 1894, he had lost much of his fortune.

1821 – Mexican Independence and the California Gold Rush

In 1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain. In 1833, the Secularization Act of the Missions was one of the significant changes implemented. The missions were closed, and their lands and livestock were redistributed. Mexican citizens, including former soldiers and settlers, received ranchos for cattle ranching. A few Gabrielino (Tongva Native Americans who lived at the missions) were granted plots of land, but these were often too small to support a family. Wealthy Californios bought these small plots and used Native Americans as labor. The last portion of the land was designated as public land for future settlers.

The Gold Rush began in the mid-1840s when Francisco Lopez discovered gold flakes at Placerita Canyon, north of Los Angeles. This first documented gold find attracted many gold seekers passing through Los Angeles on their way to northern California.

During this period, Californio ranchers prospered by providing meat to the growing mining population. However, the severe drought of the early 1860s devastated the cattle industry, leading many ranchers to bankruptcy. As the social influence of Californio ranchers declined, new settlers and investors brought significant economic and urban changes.

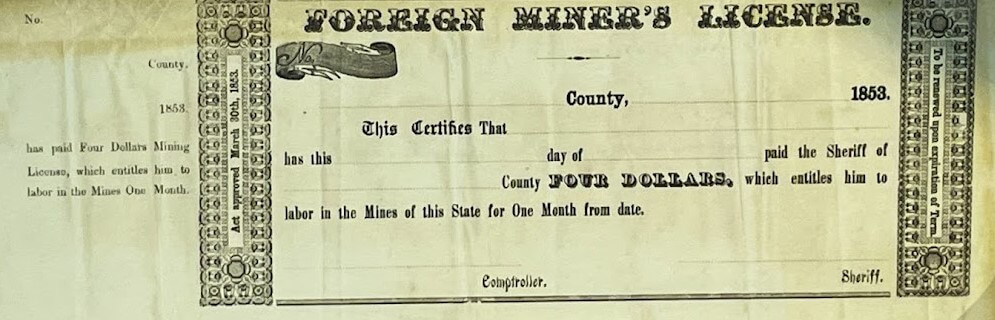

Regrettably, the increased diversity from the influx of gold seekers significantly heightened discrimination, marginalization, and racial hierarchies. White American politicians enacted laws that barred non-whites from mining gold and carrying arms. As an example, the Foreign Miners’ Tax of 1850 imposed a monthly tax of $20 on foreign miners. It was later modified to exempt “free white persons.”

1848 – The United States: An American Takeover

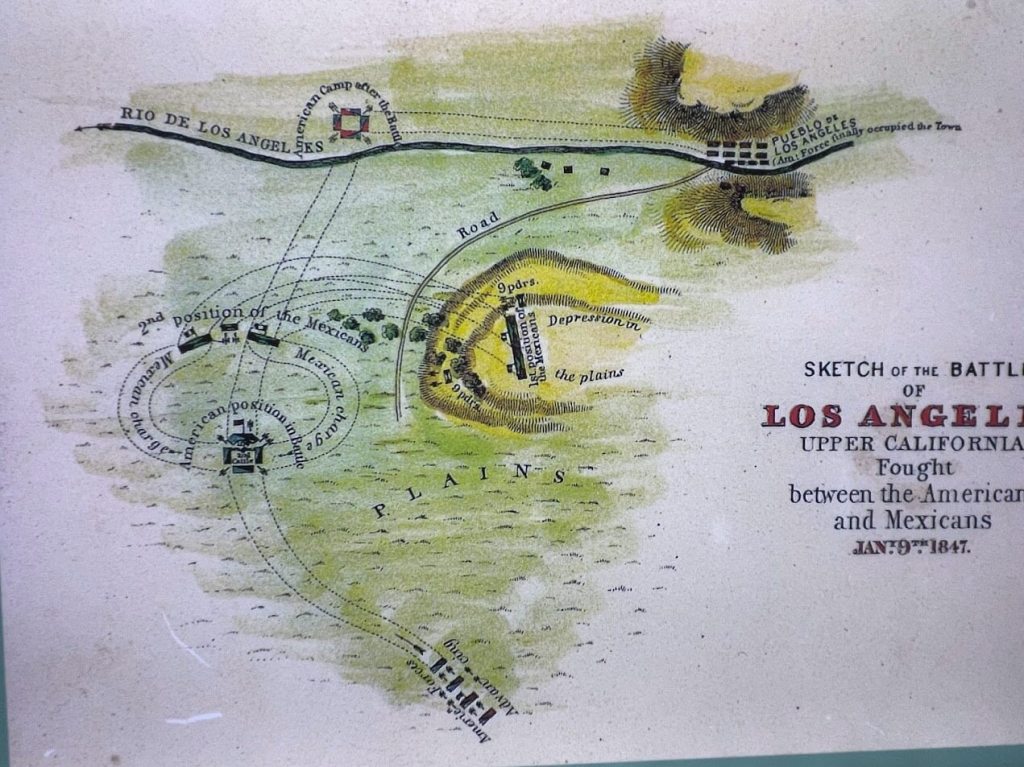

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) opposed Californios (Mexican residents of California) and Americans. While Governor Pío Pico traveled to Mexico to seek assistance in raising an army, his brother Andrés Pico led battles in Los Angeles. On January 13, 1847, after another battle was lost by the Californios, Andrés Pico and Captain John C. Frémont signed the Treaty of Cahuenga. The “Capitulation of Cahuenga” was an informal agreement between the rival military forces.

The Mexican-American War officially ended a year later with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This treaty, signed by Mexican officials, ceded Mexico’s Alta California territory to the United States.

Following this treaty, the U.S. Congress enacted the Land Act of 1851. Californios and Native American landowners were required to prove the validity of their land grants from Spain and Mexico in court. Due to a lack of documentation, high legal fees, and construction costs, many lost their land and faced bankruptcy. Consequently, the lands were redistributed to new American settlers and investors.

Did you know?

The U.S. Congress rejected Andrés Pico’s bill to divide California, which aimed to reduce tensions between whites in the north and Mexicans in the south.

The current California State flag is patterned after the Todd Bear Flag. The latter symbolized the American settlers’ rebellion against Mexican authorities during the Bear Flag Revolt in 1846. The grizzly bear on the flag represents “strength and unyielding resistance.”

1910 – Immigration

At the end of World War I, immigration from Europe decreased significantly. With the economic development spurred by the expansion of railroads, building construction and trades, and agriculture, the U.S. Secretary of Labor encouraged Mexican immigration. For Mexican agricultural workers, literacy tests and taxes were waived. It is estimated that from the 1910s to the 1920s, over 1 million Mexicans immigrated to the United States.

By 1920, many immigrants brought their families, adding women to the workforce. In the 1930s and 1940s, women worked in food-processing companies handling fruits, fish, and vegetables.

Facing discrimination, poor working conditions, and unfair wages, immigrants in California also suffered from segregation in schools, housing, employment, and public spaces. For example, Compton, Huntington Park, and Slauson were neighborhoods restricted to whites only.

1930 – Deportation

During the Great Depression (1929-1939), the US economy suffered a severe reduction in jobs. To preserve employment for American citizens, federal, state, and local governments deported many Mexicans. Although the exact number is unclear, it is estimated that around one million people were deported, with over 400,000 of Mexican descent being expelled from California alone.

Officially called “repatriation,” this mass deportation was unconstitutional, as 60% of those deported were U.S. citizens. In February 1931, a raid on Olvera Street in Los Angeles resulted in the deportation of 400 people of Mexican origin.

Article based on my visit in January 2022

Ready to explore?

Plan your visit:

- Location: LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, 501 N Main St., Los Angeles, CA 90012

- Hours: 12:00 pm-5:00 pm Wednesday-Sunday.

- Admission: Free

- Duration: I spent 1 hour discovering it.

- Parking: paid lot and metered street parking

- More information is available at https://lapca.org/

If you enjoyed this post, please comment and share it with a history lover.